This month's Frame: Posthumanism and why business should stop being user-centric

Posthumanism reveals the problems and limitations of user-centred thinking and unlocks the potential of non-human agents.

Are users the centre of the universe?

An average US smartphone receives 46 notifications every day. Notifications are central to the design of most apps and platforms. The assumption is that by placing the user in the centre of the universe and addressing their need for timely reminders and relevant information, notifications drive usage and interaction. However, while each user-need may be valid on its own terms, issuing notifications to address multiple user-needs simultaneously creates unintended consequences. Some people turn their notifications off, others ignore them and some let them pile up in whatever way their phones allow.

When notifications strike back: the need to adopt a symmetrical approach

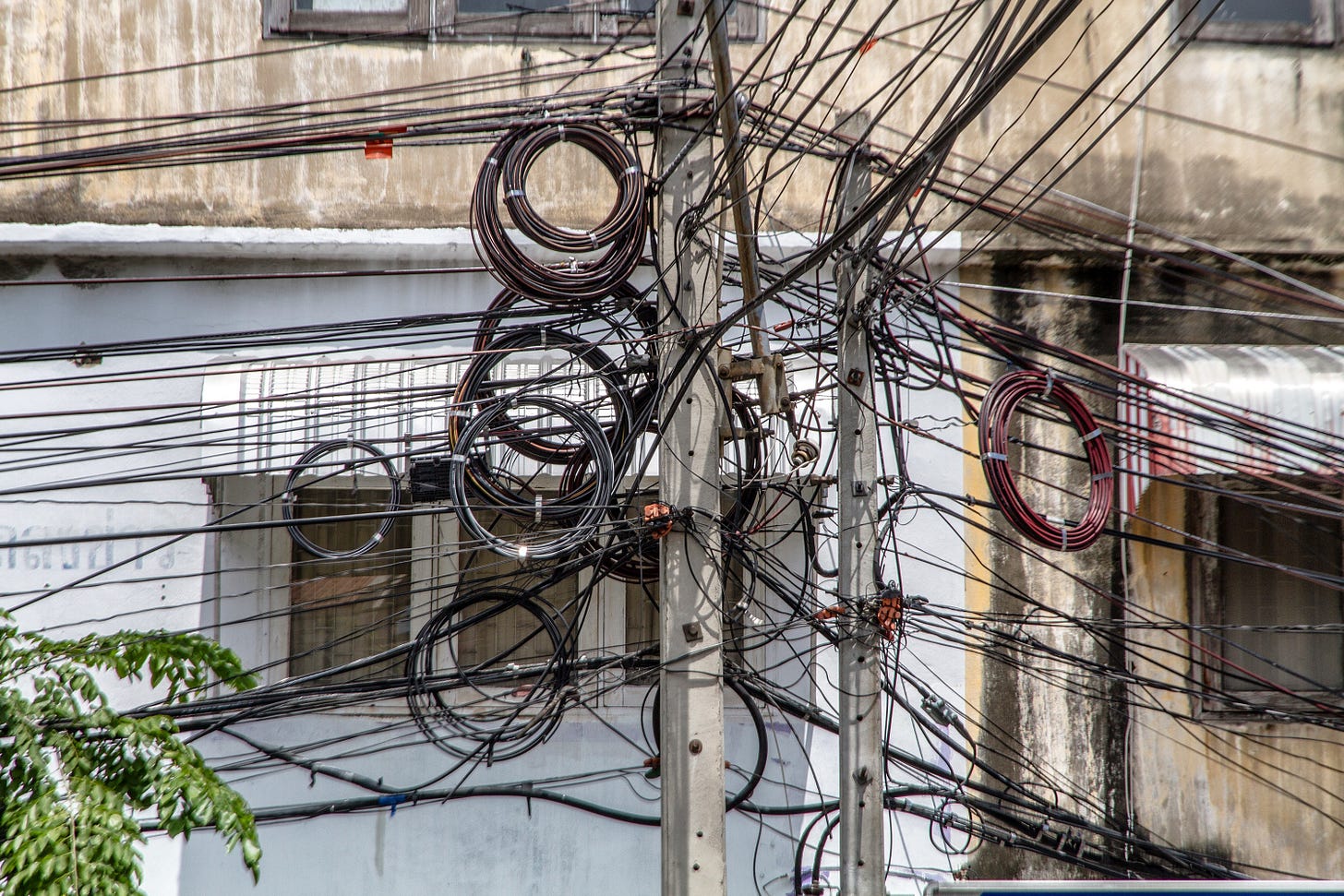

There is a common assumption that technology ought to be subordinate to individual users and serve their needs—a belief that finds its fullest expression in “user-centred design”. However, this focus on the user prevents us from seeing technology as an agent in a complex network of other agents, human and non-human. More importantly, it obscures the fact that we are not just using technology, we are entangled with it and other creatures, objects and environments. While we expect computational and automated technology to be efficient, it may actually create lots of inefficiencies if this wider network of agents is ignored.

Consider the blue tick on WhatsApp. This notification indicates that a message has been opened. However, it can affect people in many unanticipated ways—giving comfort, causing anxiety or changing power dynamics between people. The simple feature can unleash an entire drama as people try to understand its context. The problem is that the blue tick is designed for an individual’s needs (arguably, only for their needs as a sender), ignoring the broader network of users, messages, media, devices, apps and other notifications. The blue tick strikes back: it keeps us up at night, makes some avoid reading messages and others disable the feature altogether.

The framework

User-centrism is based on the assumption that there is a fundamental divide between humans and nature, and that human needs, desires or goals are of primary importance. This bias has translated into other asymmetries which have permeated culture, science and politics. For example, the mind being considered superior to the body, and scientific or technical knowledge being seen as more valid than other types of knowledge.

An alternative approach has emerged in recent years in the discipline of anthropology: posthumanism. At its core is a radically symmetrical approach to all kinds of actors, human and non-human (including living organisms, objects, technology). It no longer sees people as the only actors with agency. Instead, the focus is on the broader network of relationships, observing how different actors work together (or not), without imposing any hierarchies.

A symmetrical approach reveals a major problem of the user-centric paradigm: when we optimise for only one actor within a complex network and ignore the needs of other actors, we create unintended consequences and externalities. The climate crisis is the most obvious, pressing and large-scale example of the pitfalls of asymmetry.

More prosaically, when we design every notification to address a single user’s need to be informed we do so without thinking adequately about the impact this solution might have on the broader network of relationships that these digital and human agents exist in.

Using the framework

In a business context, we’re already used to thinking of the needs of various stakeholders. A truly symmetrical approach would suggest broadening that definition to what Bruno Latour calls “the Parliament of things”: non-human stakeholders, such as other creatures, the climate, digital and non-digital tools and devices (like the blue tick). It would explore how they cooperate, where there are tensions, and ask what would be the outcome if we optimised for the needs of multiple actors instead of just one?

For many, this approach is hard to swallow. Letting go of the idea of human exceptionalism means letting go of the right to use nature and technology indiscriminately to meet our needs. But we are not just users. We are agents in networks of agents. Anything we experience and learn is a result of our interactions with the world and hybrid (human and non-human) networks. It’s time to start thinking symmetrically.

Iveta Hajdakova, Senior Consultant

News

The Stripe Partners team is growing.

We’re hiring for a Senior Consultant and Data Strategist at a time of significant growth. If you would like to find out more about these roles, or know someone who would be a good fit, click the links above.

We’re sponsoring, attending and presenting at EPIC 2021 next week.

We’re holding an Ask Us Anything session where you can find out more about who we are, how we work and anything else you’re curious about, on Tuesday 12 October at 4pm BST. We hope to see you there.

I find this comparison to be based on a narrow interpretation of HCD focus. There has been much written and years of practice that demonstrate many HCD academics and practitioners advocate for balancing what people desire with business viably and technical feasibility.

Realizing that non-human entities may (but not necessarily do) have agency (and what kind, then?) and are interconnected is one thing, but treating all actors, human and non-human, as equal (which is what the term symmetry suggests) is something else. To do that can have dangerous consequences, as humans may become seen as disposable as anything (which is, as we can notice, already often the case). What is cared for/about might shift more easily then - should businesses care about humans? Or technologies? Their economic growth? Or the health of all living beings? After all, it's all about symmetric actors, right? :)