This month's Frame: how heterarchy can help us put hierarchy in its place

A framework that shifts perspectives by taking into account multiple relationships and interdependencies.

Some ideas about how the world works feel so obvious as to be beyond question. They have taken on a sense of appearing to be part of the natural order of things. Hierarchy—an arrangement, ranking or classification of people or things on the basis of their importance or value—is one such idea. Hierarchies are evident at scale in societies when classes or castes of people are ranked on the basis of some factor or other (be that wealth, cultural capital or purity). And secular hierarchies are often supported by hierarchies in the realm of the sacred, symbolics or spiritual.

The idea of hierarchy seems so natural because the criteria by which things are ranked have themselves a tendency to appear innate. Consider, for example, class distinctions. These are often expressed in hierarchical terms (“She married beneath herself”, “He’s a social climber’), but are constructed, communicated and cemented by a bewildering array of cultural distinctions that show up sartorially, linguistically, symbolically and through social practice. The result is that the hierarchical ranking of people takes on a logic of its own that is difficult to see for what it is – an invention.

Ideas and practices informed by hierarchy are common in the world of business too. Hierarchy informs organisational design, decision making and cultural practices. These practices naturalise hierarchy. And hierarchy is a feature of the methodologies and frameworks used by consultants, like “need hierarchies” and the propensity for rankings of things like product features or benefits.

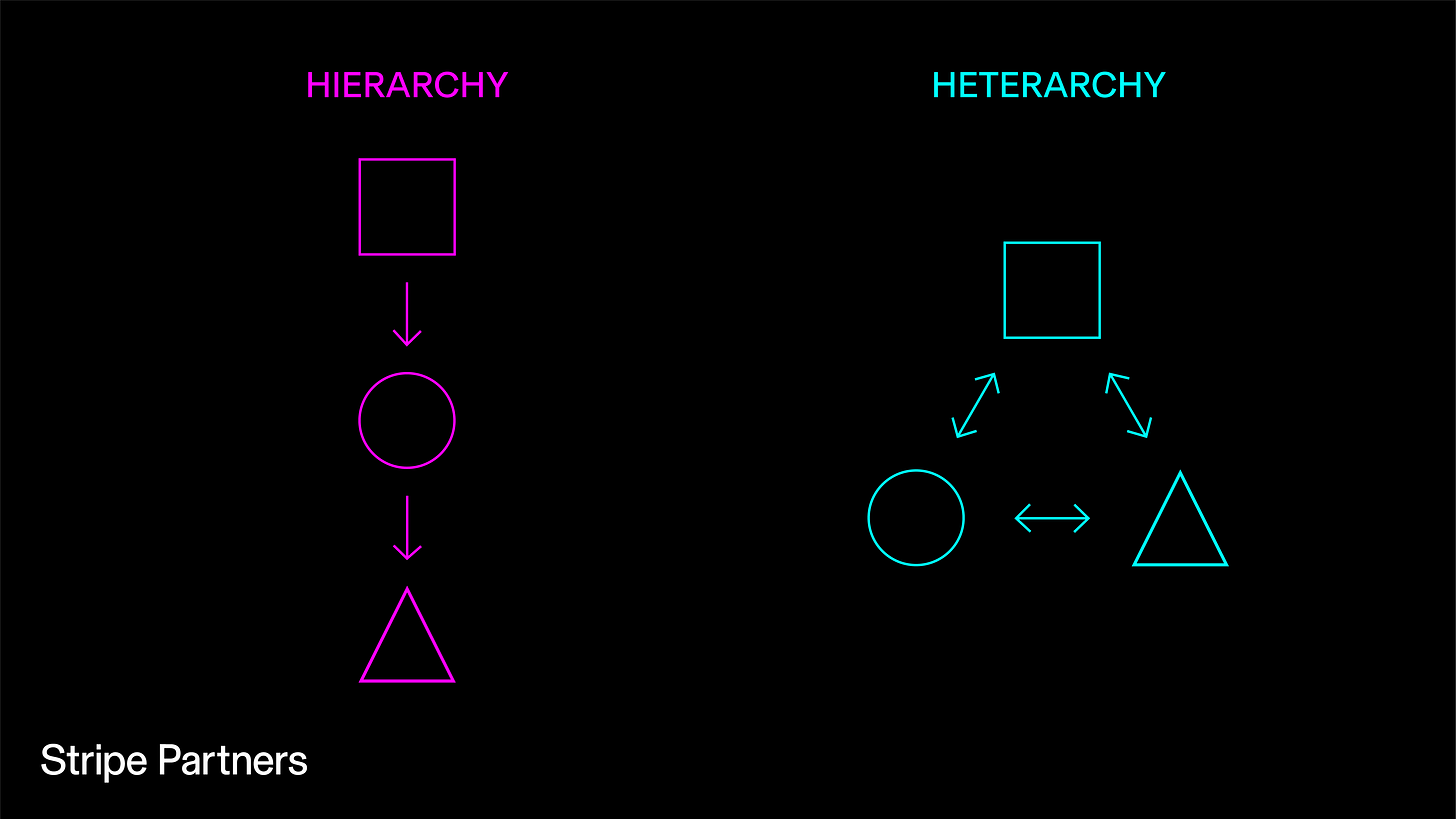

What results from the fact that hierarchy is an unquestioned element of the grammar of human existence? It’s that hierarchy has an outsized impact on how we think about culture, society and organisations. But many social, cultural and natural forms are not organised hierarchically. A different lens—that offered by the concept of heterarchy—provides more than a corrective to our obsession with hierarchy. It helps explain more fundamental processes at play in the natural and social world.

The framework

The origin of the idea of heterarchy is a 1945 paper by neurophysiologist and cybernetician Warren McCulloch. In it he explored the topology of neural nets and demonstrated that the human brain is not organised hierarchically but heterarchically. Heterarchy then is the “relation of elements to one another when they are either unranked or when they have the potential to be ranked in a number of different ways.” McCulloch’s work highlighted the existence of systems in the natural world that display structure, or some form of order, without being hierarchically organised.

American philosopher Jay Ogilvy captured the essence of heterarchy by using the game “Rock, Paper, Scissors” to illustrate the way that elements can be differently ranked according to various metrics.

Paper covers rock, rock blunts scissors and scissors cut paper. There can be no hierarchy since each element in the game has different properties.

Another example might be similar sized cities in a nation—one might draw its power from being a military base, another from being administratively important and a third from being a mercantile centre. They are important for different reasons. It makes no sense to rank them.

Political forms, like the US constitution, are often organised along heterarchical lines: no single branch of government has supreme authority over others in all circumstances. A heterarchy possesses a flexible structure made up of interdependent units. The relationships between those units are characterised by multiple linkages that create circular paths rather than hierarchical ones. Yet, heterarchy and hierarchy are not mutually exclusive. Both might exist in parallel to each other, or a heterarchy be subsumed by a hierarchy or may itself contain hierarchies.

Heterarchy is a characteristic found at the level of neurons, in the natural world and in the ordering of human affairs. But it’s crowded out by the dominance of hierarchy in how we look at the world.

Using the framework

The idea of heterarchy offers a perspective shift rather than providing a simple “copy and paste” model to transpose onto a social context or cultural phenomena. It’s a suggestion to acknowledge that complex organisation, ecosystems or ecologies might not always have a top and a bottom, that there’s not always a “king of the jungle”, but instead a more complex, fluid set of relationships between elements or organisms where superiority or inferiority might be circumstantially or dynamically defined. Organisations focusing on a single KPI (such as a Net Promoter Score) show the proclivity to obsess about one metric over all others on the basis that this single measure is not just important, but of primary importance.

Hierarchy dominates in artefacts such as product feature rankings in a way that is often unquestioned. On what basis is the ranking being constructed—value, utility, ease of use? All may have value but the selection of one basis for ranking excludes others and the possibility that a combination of factors might provide a fuller picture. For example, ranking features in terms of their perceived value has the potential to wash out context (is feature A the most prized in all contexts by all users?) and to flatten out the relationships and interdependencies of different features.

The pursuit of a tidy hierarchy creates an unrealistically simple picture of individual elements. In contrast, a perspective informed by the idea of heterarchy doesn’t seek a single point of view but one informed by multiple concerns that emerge or recede from view according to our vantage point. It’s a less tidy view of the world, but by resisting the desire to order things on the basis of one characteristic or other it creates a more authentic view of the real order of things.

News

Agile teams, submissive organisations: does Agile hamper innovation?

Sign up to join us for a webinar at 4pm BST on Thursday 18 May where we'll discuss the origins of Agile, what it means for organisations today and how to fulfil its promise while avoiding the pitfalls.

The Stripe Partners team is growing once again.

We’re hiring for a Senior Consultant and Junior Consultant at a time of significant growth. If you would like to find out more about these roles, or know someone who would be a good fit, click the links above.