This month's Frame: designing virtual “taskscapes” to build a better Metaverse

A framework that can help create a virtual world that people want to live in.

The Metaverse—ie. a highly immersive, highly-connected virtual environment—is at a crossroads. Lately, it seems that talk about the Metaverse is being drowned out by the wave of discussions on the topic of generative AI. In fact, Microsoft is pulling out of the Metaverse race to double down in this area.

Yet Meta has still bet big on the technology, and new VR hardware continues to be developed—such as the recent PSVR2 and HTC Vive XR Elite. There’s still a lot to play for, and designers working on creating virtual environments for the Metaverse need to make sure that people use them and keep using them.

How to do this?

There are numerous theories from the world of human-computer interaction and design that are helping people build the Metaverse—such as user-centred design, spatial cognition theory, affordance theory.

However, many of these approaches, particularly when it comes to designing virtual environments with a specific purpose in mind (eg. digital offices) tend to fall short. They occur within a hierarchy where the designer is the architect of an environment, trying to create perfect worlds to “nudge” people to perform activities intended for them.

To understand why these types of approaches often fail, we can turn to anthropologist Tim Ingold, whose work on how people relate to their environment over time—specifically, his ideas of the “taskscape” and “dwelling perspective”—can inform the development of virtual worlds.

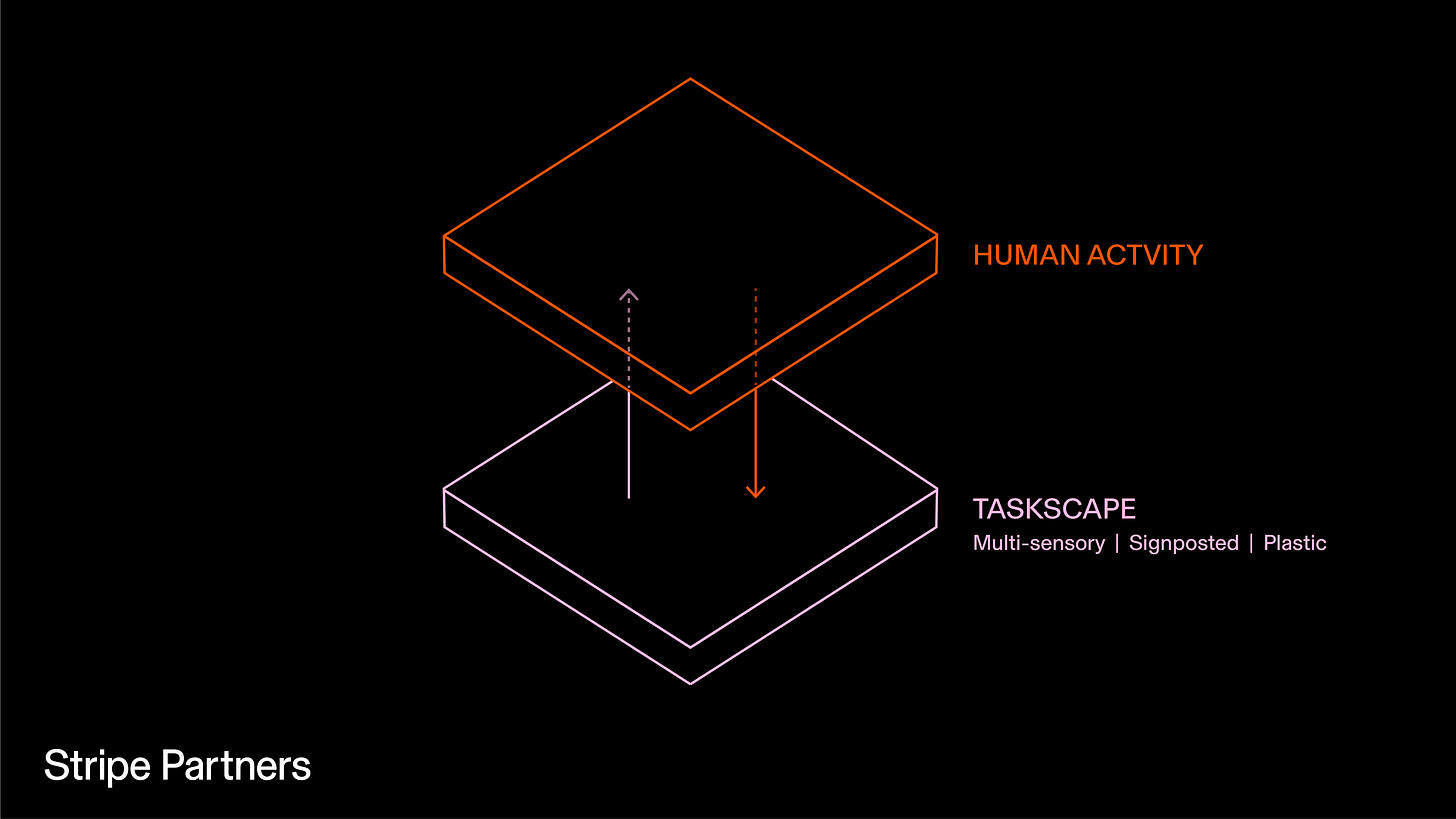

The framework

Ingold distinguished between a physical environment and one that is encoded with social meaning. He coined the term “taskscape” to describe the latter. A taskscape refers to the way in which people shape, and are shaped by, the world around them as they engage in various activities and tasks.

When it comes to understanding a taskscape, Ingold emphasises the importance of going beyond the visual—in other words, adopting a multi-sensory approach. Sound can be more important than vision, because often auditory information conveys what’s going on right at this moment, whereas purely visual information can lack immediacy.

Think about a restaurant—what tells you more about the “vibe” of the place, a still photo of diners eating, or the sound of chatter and clinking cutlery? This overemphasis on the visual is an important consideration when it comes to designing virtual environments, which tend to prioritise visual fidelity as a way to elicit immersion.

Another important aspect of a taskscape is the level of signposting within it—the people within the taskscape should find it easy to “read” how to use their environment. Think of the way a football pitch looks and feels—often muddy, long enough grass to grip and dig in but not so long that it drags—it nudges you to run. By contrast, the intimidatingly-manicured surface of a golf green encourages you to walk on it.

Lastly, the taskscape needs to have a degree of plasticity to it. As people engage in tasks and activities, they leave traces of their presence in the environment, such as footprints, tools, and other artefacts, which shapes the environment around them—like “well-trodden paths” becoming established routes. The environment displays signs of the past, and often exhibits seasonality.

This is not to say that a taskscape is totally fluid and malleable. It needs to be solid enough to shape people’s behaviours and activities in turn, creating a feedback loop between people and the world around them.

Ultimately, taskscapes lead to humans developing close relationships with their environments, resulting in what Ingold called the “dwelling perspective”. This was his way of talking about how people exist within their homes—the emotional, cultural and symbolic centre of their lives. Consider the phrase “a house is not a home”—Ingold would say that the house is a building, whereas a home is a dwelling.

Using the framework

So what are some principles that designers can use in order to incentivise people to form deep connections and “dwell” in online spaces?

We believe that virtual taskscapes need to be:

Multi-sensory—allow users to engage with virtual environments with many different senses and types of information, rather than prioritising visual fidelity. For example: haptics, proximity audio. These can help convey the “life” of a space far better than visuals alone.

Signposted—make the environments interactive and engaging, so that their purpose is suggested to a user. Carefully consider virtual exterior and interior architecture, how sound echoes, background music etc. Video game tutorial levels that show “how to play” are a useful source of inspiration for this.

Plastic—allow people the space and tools to define their own environment rather than design highly-choreographed settings for them. To use another concept from gaming, ensure there is a high “skill ceiling” that lets people develop mastery when it comes to building their world—think of the possibilities that are found within sandboxes such as Minecraft, Roblox etc.

By using these principles, designers can create virtual experiences that go beyond delight, and become dwelling places. For this bold new technology, the ultimate criteria for success is this: will people weave it into the fabric of their lives?

News

Help us keep our writing relevant and useful by answering a few questions on what you think of Frames. It will only take a few minutes and your responses are greatly appreciated.

Interested in collaborating with us? We're looking for more freelancers to join our freelance network.

Frames is a monthly newsletter that sheds light on the most important issues concerning business and technology.

Stripe Partners helps technology-led businesses invent better futures. To discuss how we can help you, get in touch.