This month's Frame: Dall-E, Jacques Ellul and Technique as Self-Service

A framework for understanding why the best known methods are now accessible to the average user

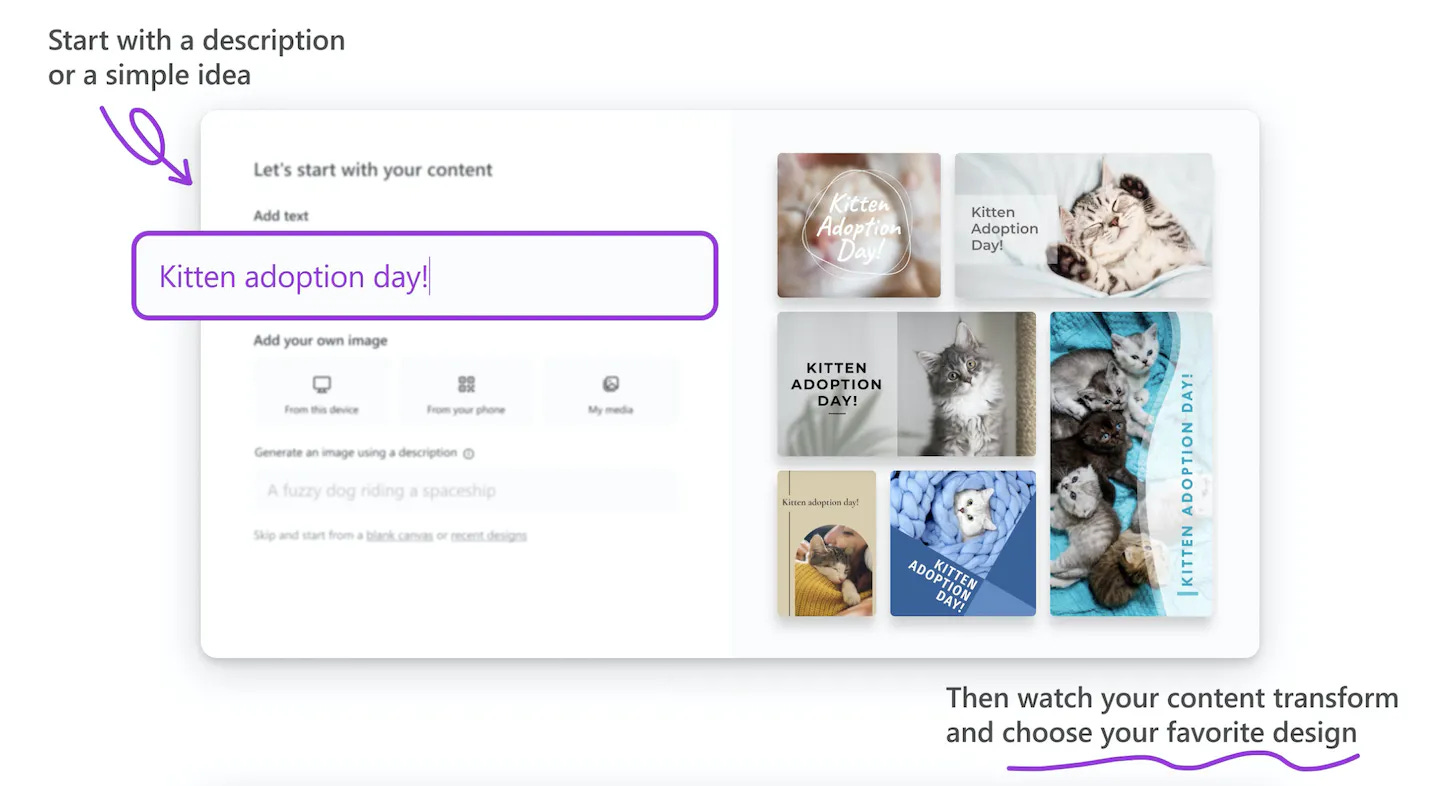

Last month Microsoft launched Designer, an app that claims to empower anyone to create “stunning designs in a flash.”

It is the latest in a series of platforms including Figma and Canva that “democratise” design; automating tasks that once required technical expertise and expensive, specialised software.

Microsoft Designer is the first to embed Dall-E, Open AI’s tool which generates sophisticated imagery based on simple written prompts. The result is impressive: a user can move seamlessly from idea to usable design, with the intermittent technical steps collapsed into a Instagram-style UI.

As a User it feels like you’re collaborating with your own personal Designer: your job is to create prompts and choose from the design options provided. But this time the feedback loop is instantaneous; the cost effectively free.

Technique and standardisation

In 1954 sociologist Jacques Ellul published “The Technical Society”, in which he outlines the encroaching influence of “Technique” on the world. For Ellul, Technique is the process by which society converges on the best known method to achieve a given task or outcome. Machines are not necessary for the realisation of Technique, but in many industries they are the end game.

Before industrialisation, fishing was a craft. For generations fishermen learned how to navigate via the sun and make decisions on where to deploy their nets based on feel and intuition. Expert fishermen were able to adapt their skills spontaneously to the weather and conditions. Improved Techniques were originated by virtuosos with decades of experience.

But because the desired outcome of most fishing activity is to maximise the number of fish caught, machine-driven techniques sidestepped more incremental human innovation. Today, 2km driftnets combine with underwater sonar and auto-piloted boats to create the best-known method. Fishermen have transitioned from craftspeople who have mastered tools, to skilled technicians operating machines.

For Ellul the human capacity for freedom and virtuosity is stunted in this process. As the market relentlessly optimises for efficiency, choices are increasingly dictated by Technique. New technology originates new and better processes that professionals must continually adapt to. A fisherman could revert to older practices, but not if they want to compete on the open market.

The framework

Ellul wrote before the emergence of software. Advances in Graphical User Interfaces, UX design and artificial intelligence are making complex Techniques accessible to laypeople. Personal Computers once required significant technical expertise to operate. Today Apple takes pride that its devices are intuitive enough to require no instruction. The SaaS industry has grown to $175 billion because advances in software and AI make it possible to automate vast service layers across professions as diverse as HR, sales, education and banking. This enables non-expert Users to “self-serve” rather than rely on expert Technicians. While Ellul perceived the rise of the Technician, we observe the rise of the User.

The rise of the User can be interpreted as the return of the Amateur. To put it in Ellul’s terms: a User is an Amateur empowered by direct access to the best Technique. Software has removed the Technician as the gatekeeper of the best known method.

Ellul lamented the loss of Craftspeople as they were gradually replaced by Technicians. Today would he be concerned by the replacement of Technicians by Users? The spontaneous creativity inspired by new technologies such as Dall-E evoke some aspects of the world Ellul valued before Technique took its grip. But he would ask: what is this creativity in aid of? As the “use cases” of these new technologies mature they will be optimised in service of particular ends. And the User, like the Technician before, will be forced to adapt to more efficient emerging methods.

Using the framework

Some industries—like fishing—have remained resistant to Users and continue to be populated by Technicians. Likewise, design professionals have relied on the complexity of their Techniques - instantiated in software such as Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop - to create high barriers to entry. But recent advances in AI and UX design are automating aspects of the role previously held to be innately human. A Designer was a Craftsperson; now many operate as Technicians. Tomorrow, with access to the latest software, Users are Designers too.

Finally, then, the question is posed: will Design Users replace skilled Designers? Here there is some hope for the experts. Techniques are optimised to achieve defined outcomes. But because what is judged good design is partly a matter of taste, these success parameters constantly shift with culture. In such a context the “self-serve” model works in narrow, incremental spaces in which the standards of good design are clearly settled. This is not good news for Design Technicians, focused on predictable design tasks.

But where judgement matters, the craft of Design is as important as ever. Not so much the technical aspects (which will be increasingly augmented), but the softer skills: a Designer’s cultural knowledge, good taste and capacity to conceptualise and narrate what is valuable are more vital than ever. Because where success is ambiguous to define, humans will continue to influence what constitutes the best Technique.