This month's Frame: AI is not your tool, it’s your plaything

A framework for understanding AI through Vilém Flusser's concept of the “apparatus”.

Some of the most pressing questions about AI are: what is it and what can it do?

The recently launched ChatGPT4.o now “accepts as input any combination of text, audio, and image and generates any combination of text audio, and image outputs.” This new, multimodal iteration of Chat GPT expands the possibilities of human-computer interactions across text, conversation, code, image, and audio. But what might it mean for our relationship with AI, how might it restructure our experience and even our sense of self?

And will it replace us?

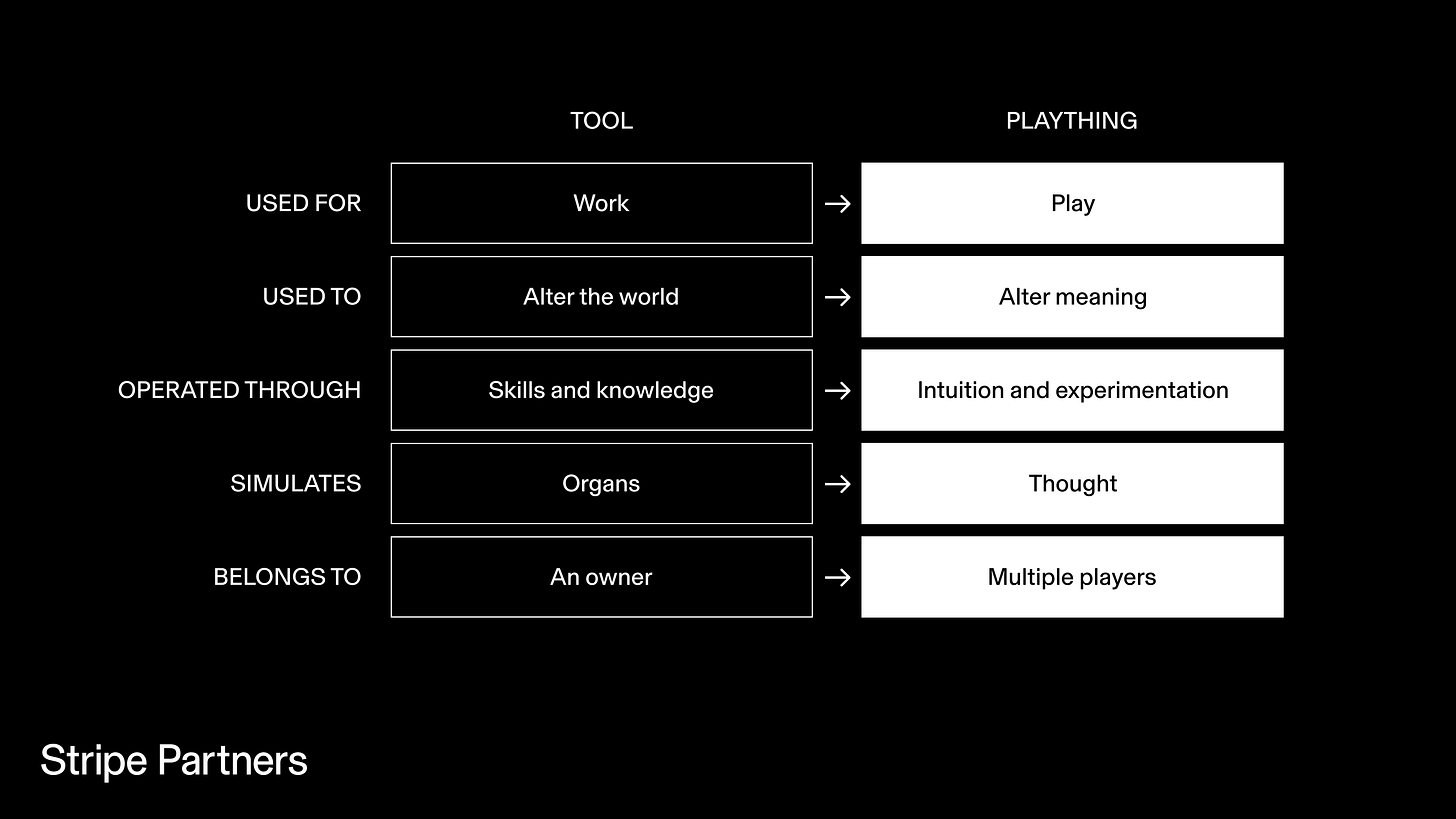

Viewing AI solely through the lens of tools and functions limits our understanding of the value of AI to labour. Within this paradigm, we are worried that AI will replace humans because it will do our work for us. However, a more nuanced understanding emerges when we explore AI using the concept of the "apparatus," as developed by the Czech-Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser, who sees the relationship between people and apparatuses through the lens of playthings and play.

The framework

In his book Towards a philosophy of photography, Flusser argues that while it may seem that a camera is a work tool that is aimed at changing the world, it should instead be viewed as an apparatus aimed at changing the meaning of the world by producing symbols. In this sense, when we use cameras, we are not shaping the state of the world, we are searching for new ways to capture or represent the world.

In its previous conversational form, the capacity of ChatGPT to generate new meaning wasn’t as obvious because it resembled the way we exchange information in a conversation. However, the latest version makes it possible to mediate across various systems of meaning. Not only can you turn your thoughts into images, you can also turn the contents of your fridge into an exciting recipe.

For Flusser, a camera mechanises the work needed to create images and thus allows the photographer to “play”. “Photographers no longer need, like painters, to concentrate on a brush but can devote themselves entirely to playing with a camera.” The focus on play in the context of automation is important for Flusser. Apparatuses synthesise and remix information, operating under the logic of combination, rather than causality. If you play with your camera’s settings, you’ll get different results, often changing the look and feel of the final image. Similarly, if you play with your prompts to ChatGPT, you’ll get different results. Flusser argues that this shift from work to play is characteristic of the information society.

Designed to function and respond automatically, apparatuses intensify the process of play, removing the importance of human intention. Indeed, an interaction with ChatGPT doesn’t start with an intention, it starts with an openness to iterate on the interaction itself. ChatGPTs responses are always different, even when given the same prompt, and one can play until something clicks. Consider also The TextFX Project by Lupe Fiasco and Google Lab Sessions, in which AI can be used to help “writers, rappers and wordsmiths” play with language. The prompt “fresh cut grass” can generate some beautiful scenes evoking feelings (“the feeling of the warm freshly cut grass between your toes”, sensory memories (“the taste of a fresh-cut piece of watermelon”), smells, sounds (“The sound of a lawnmower buzzing in the distance”), or colours (“the sight of a green lawn with a fresh mow”).

To explain how different the act of photography is compared to more instrumental acts, Flusser compares it to going on a hunt in which “photographer and camera merge into one indivisible function. This is a hunt for new states of things, situations never seen before, for the improbable, for information.” Play is immersive and Flusser goes as far as to suggest that in the future, people will lose themselves in play. In his book Into the Universe of Technical Images, Flusser predicts:

“The person of the future will be absorbed in the creative process to the point of self-forgetfulness. He will rise up to play with others by means of the apparatuses. It is therefore wrong to see this forgetting of self in play as a loss of self. On the contrary, the future being will find himself, substantiate himself, through play.”

Using the framework

So how can the concept of the apparatus help us understand what is at stake for people, culture and organisations as ChatGPT not only rolls out new features, but generates new possibilities and restructures our experiences, cultures and sense of self.

To begin with, the apparatus helps us identify a shift we need to make in our thinking. Apparatuses are not tools, they are playthings that represent a larger shift in our relationship with technology.

While so much conversation about AI and LLMs has been focused on work and tasks, we might want to explore more playful use cases, and consider that even work might adopt more and more characteristics of play. The interactions with AI might need to be designed using the principles of PX (player experience) to support a back-and-forth interaction that fosters the state of flow, instead of borrowing design inspiration from hierarchical relationships, especially that of a master and an assistant.

The dominant narrative around AI, and around technology more broadly, still posits that humans are masters of technology and that technology should serve them and liberate them from mundane tasks. Thinking in terms of human superiority, domination and labour only strengthens the anxieties around technology getting out of its masters’ control, rising against them, or simply replacing human workers by being better and more efficient at their jobs and tasks.

The concept of the “apparatus” enables us to shift the narrative around AI and the role it should play in our lives. AI is not a mere extension of human labour. It is an apparatus that disrupts and reshapes our production of meaning and challenges the existing boundaries between work and play. Rather than replacing us, AI will play a new role in mediating our interactions with the world. In the world of synthetic (synthesized, remixed) information, the self will lose the sense of ownership, authority and individual creativity and become more porous, more ready to be immersed. Such a self will need new forms of education and guidance so they become better as apparatus operators and players. Ultimately, these players will look for new opportunities to use their apparatuses to remix information to create and accumulate new forms of value. Will it be new knowledge, new experiences or new playthings?

Frames is a monthly newsletter that sheds light on the most important issues concerning business and technology.

Stripe Partners helps technology-led businesses invent better futures. To discuss how we can help you, get in touch.