This month’s Frame: Using Bernard Stiegler’s pharmacological approach to heal from digital fatigue

A framework for designing digital products with therapeutic outcomes.

In 2009, Apple coined the phrase “There’s an app for that,” celebrating the endless possibilities for “disruptive” innovation enabled by the smartphone. There was excitement about digital experiences that upended decades, even centuries-old ways of doing things. Take dating: in 2013, swiping on Tinder felt like being part of something revolutionary. By 2025, what once seemed like an exciting solution to the problems of single people, has now become a problem for single people and the cause of jadedness, disillusionment and exhaustion. Many are turning away from dating apps.

Online dating is part of a broader fatigue with digital solutions and algorithmically-driven experiences combined with a nostalgia for IRL experiences and analog products. In 2025, young people are excited when they realise “there’s a dumb version of that”.

However, this digital fatigue is not widely understood. What might lie behind people’s shrinking appetite for technology, and how can we account for this when we ask “what’s the app for that?” or “what features should we develop?”

The framework

To understand this growing ennui with digital products, the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler offers a useful lens, through his writings on technology and “individuation”—the process by which people “become themselves.”

According to Stiegler, humans have always relied on technology to evolve; not just biologically, but culturally and psychologically. Tools, language, writing, music are all examples of “technics” that allow us to store language, share experiences and reflect on who we are. They make individuation possible because they help us step back, reflect and grow.

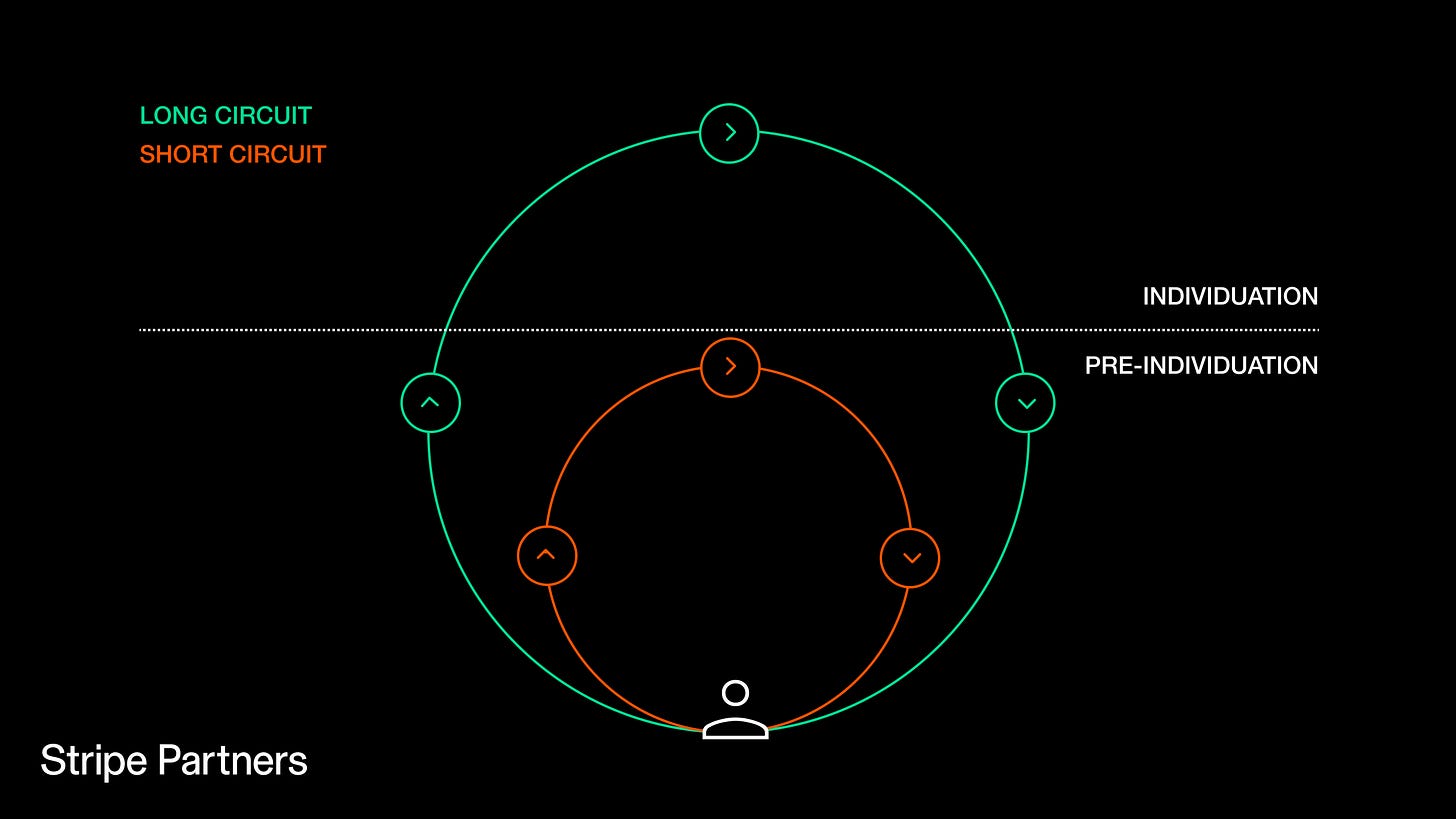

Some technologies enable and encourage “long circuits” of individuation, which are slow, reflective processes that help people make meaning over time. Think of learning to play an instrument, following a musician’s career, or participating in a fan community. These long circuits require attention, participation, and reflection—and often give people a sense of meaning and purpose.

By contrast, many digital products today create “short circuits”. These bypass the long, messy, effortful process of meaning-making and instead deliver instant gratification—a match on Tinder, a like on Instagram, an endless feed of content.

In the language of user journeys, short circuits leverage triggers and drivers before the user starts considering other options or changes their mind. Unlike long circuits, which take time and are unpredictable, short circuits are much simpler, less idiosyncratic and easier to gratify at scale.

These experiences tap into what Stiegler calls our "pre-individual” drives—our basic impulses and reactive desires that don’t require reflection or effort. The more we engage with short circuits, the less space there is for longer-term, meaningful engagement.

Stiegler’s short and long circuits are a good way of understanding “digital fatigue” and the structural exhaustion caused by being trapped in “short circuits” that never allow us to individuate and fully become ourselves. Over time, this can lead to feelings of alienation, loss of desire, even despair—and product rejection.

Using the framework

A pharmacological approach to technology recognises that technology is both a poison and a cure when it comes to individuation. The same tools that can exhaust and disorient users can also be reimagined to restore attention, meaning, and individuation.

For businesses, product teams, and designers this approach opens up 2 key strategic opportunities:

1/ Disruption is an opportunity for restoration

Much of the tech industry has focused on disruption as a positive force, shaking up old habits and creating new markets. But disruption also causes losses: broken habits, fragmented communities, weakened relationships—these losses leave people vulnerable, fatigued and trapped within “short circuits”. Businesses that recognise what has been eroded can make products that can repair or restore long circuits of engagement. We are already seeing signs of this, for example:

IRL experiences are making a comeback, like Tinder partnering with Runna to encourage singles to meet up while running

New platforms like Weverse to help artists reconnect with fans in more curated, less algorithmic ways such as artist-led listening parties

Media brands like i-D magazine are returning to physical formats to offer tactile, meaningful experiences

These aren’t just nostalgic gestures, but rather signs of a growing hunger for technologies that support reflection, connection and care—long circuits.

2/ Optimise for outcomes, not engagement

Short-circuit products are often optimised for one thing: keeping users engaged. However, we have seen that this strategy is unsustainable, leading to fatigue and backlash against tech. Instead, product teams can design for outcomes that support individuation and well-being. Digital products don’t have to be designed purely to maximise engagement; they can be designed to deliver therapeutic outcomes. This means that digital products should not aim to be everything to everybody but, instead, should support users in their individual circumstances and empower them to live better lives. A great example of this comes from more established tech products, such as video games, that are aimed at broader outcomes, including relaxation, therapy, learning and mental health.

A pharmacological approach to technology asks us to move beyond simplistic narratives of progress and disruption. It invites businesses and developers to think more critically about what they are building, how it shapes human experience, and what futures it makes possible. Technology is not neutral—it is both poison and cure. By acknowledging its dual nature, we can begin designing in ways that foster individuation and give people a sense of meaning and purpose.

Interested in exploring similar topics further? Explore our archive of past Frames for fresh perspectives:

Personal growth apps aim to help people develop in various aspects of their lives but often fall short in helping people to make lasting change. We explore how schema-based pedagogies can support this here.

In our piece on improving game development, we explore how a “discursive” approach to the past, present and future can help game developers design in ways that inspire devotion in fandom and can help retain cultural momentum over time.

In our piece on IQ and EQ, we explore how these two useful, if admittedly flawed dimensions of human experience can help us design AI experiences that meet people where they are.

Frames is a monthly newsletter that sheds light on the most important issues concerning business and technology.

Stripe Partners helps technology-led businesses invent better futures. To discuss how we can help you, get in touch.